In South Tyrol, a European project is giving dusty photos a new lease of life

A cross-border project organised by Austrian Tyrol and Italian South Tyrol is bringing historical photos out of the archives and giving them a second life, through digitisation, sharing, virtual exhibitions and an app.

Bolzano (Italy), Lienz (Austria)

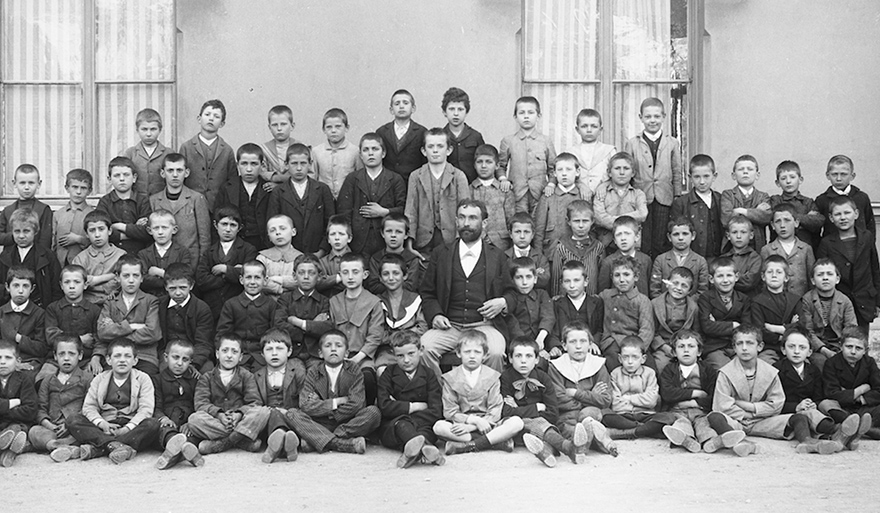

Until its closure in 1986, it was customary for schoolchildren from Bolzano (or Bozen, in Italy’s historically German-speaking South Tyrol) to visit the Waldmüller photographic studio for the regular class photo. Every year Anna, one of the daughters of Hermann Waldmüller – who set up the business that bore his name at the end of the 19th century – would arrange the children in neat rows in front of the camera bought by her father.

The photographic heritage of the former Waldmüller studio in the Fleischgasse – today Via Museo – in Bolzano is part of the 12,000 photographs digitised as part of the EU Interreg project "Living Silver: Cultural Heritage Photography" ("Argento vivo: Fotografia patrimonio culturale"), coordinated by eight partner organisations from Italy and Austria and financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

One of the aims of the project, which ended in 2019, was to digitise the photographic collections held by the four main partners: the Tyrolean Archive for Documentation and Photographic Art (TAP); the City of Brunico (Bruneck) and the Film and Media Office and Museums Department of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano.

Since 2000, the rich photographic heritage of Hermann Waldmüller's studio has been in the possession of the Film and Media Office of the Province of Bolzano. Descending into the basement of the provincial building on Andreas Hofer Street in the centre of the South Tyrolean city, one has access to the "treasure trove" of the Film and Media Office. This archive contains around 300,000 photographs including slides and negatives.

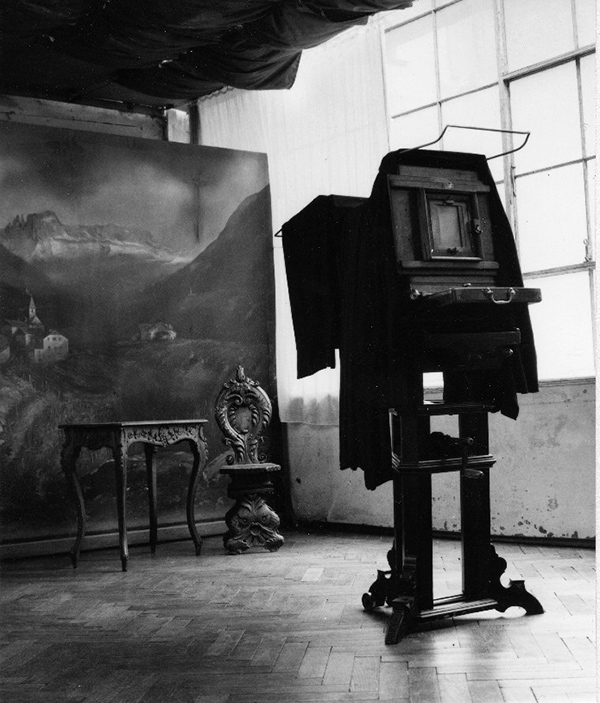

Stored in compactable archives are the photographic portraits – with their glass-plate negatives – taken by the Waldmüller family during the studio's lifetime, from 1896 to 1986. In addition to the photographs, there are objects and tools of the trade that were once part of the studio's furnishings.

Marlene Huber, the archive’s director, carefully handles the glass negatives, pulling them one by one from the shelves. They depict women in tight corsets and wide skirts. In the basement room, conversations in Italian and German flow over each other, as is the custom in this part of Italy. South Tyrol – or Alto Adige – was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1919.

A treasure to be digitised

Anna, one of Hermann Waldmüller's nine children, took over the family business in 1970, the year her brother Franz died. He had taken over the business in 1902, after the death of his father.

"My aunt Anna did not have the training to be able to run the business, so, in the 1970s, she had to take an exam in order to continue as a photographer," Stephan Waldmüller recounts. It was his and his brother Georg's decision to donate everything in the family's studio, now a private home, to the province.

When asked what he thinks of the fact that the work of his grandfather, uncle and aunt has now been digitised – thanks to the Living Silver project – and is available free of charge in a database of images under a Creative Commons licence, Stephan says: "In my opinion, the studio is part of Bolzano's history. There were other photography studios, but this one was the best known and most respected. And everything has been preserved as it was, including the tools and lamps."

All images collected and digitised during the project's lifetime – between 2017 and 2019 – are available with their metadata under a CC-BY licence on the Living Silver portal. This licence allows copyrighted works to be used, even for artistic or commercial purposes, as long as the authorship of the work and the archive to which it belongs are attributed.

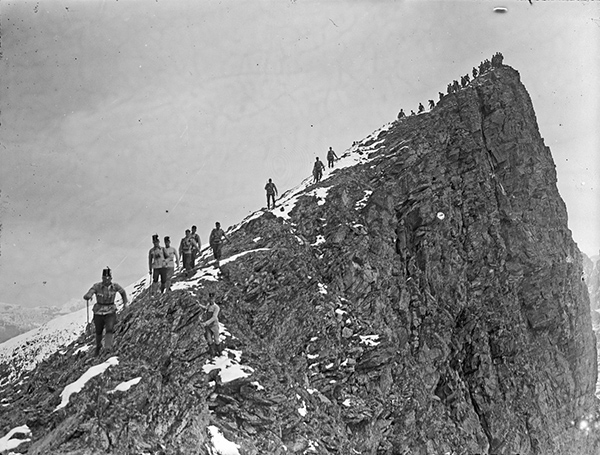

In this way the project has made accessible, free of charge, 12,000 photographs of the Tyrol and South Tyrol from the period between 1880 and the last years of the 20th century. An invaluable cultural inventory has thus been opened up to the local community and made available for a wide variety of purposes.

"We have been in possession of the Waldmüller collection for a long time but until the beginning of the Living Silver project we had only done ad-hoc digitisations without a complete strategy. So we thought that with European financing we could dedicate ourselves to this and take on staff to catalogue these photos, which is the most important aspect," explains Marlene Huber.

"Thanks to the European funds, we worked with young people, who were passionate about historical photos, and they worked right here, in this room [...]. It was almost an assembly line," she laughs. She is sitting in a room in the provincial building, among banquettes arranged in a horseshoe configuration.

In addition to digitisation, the ERDF’s €670,000 grant helped pay for five public workshops. They were led by experts of different nationalities and were open to all those interested in taking care of family photos or who simply wanted to acquire new skills in the fields of historical photography, copyright, archiving and digitisation of photographs.

Plunging into the past with an app based on historical photos

Lienz is a municipality of 12,000 inhabitants in East Tyrol, just a few kilometres from the Italian border. On the way from the train station to the Tyrolean Archive for Photographic Documentation and Art (TAP), one inevitably ends up at Johannesplatz. The square is among the historical sites in Bolzano, Brunico and Innsbruck that feature in the Timetrip Pics app, developed by the Living Silver team with the help of a European grant.

In addition to the traditional uses of historical photographs in museums, exhibitions or history books, the challenge for the four project partners was to find innovative ways of presenting historical photographs to the public. Using 360° panoramas and timeline views, the app shows how squares and buildings looked in the past. The phone recognises the places in the frame and restores the appearance they once had, making use of historical photographs.

In addition to the app, the project also set up two virtual exhibitions. They "were something relatively new at the time, at least for the archives of the Tyrol and South Tyrol regions," explains Martin Kofler, director of the Lienz TAP, the project's lead partner. The exhibitions in question are accessible on the Living Silver portal.

One covers the photo archive of the Kneußl family, whose shots date from the 1880s to the 1960s. The other is entitled "Piste!: Photographic impressions of skiing in Tyrol, South Tyrol and Trentino, 1913-1997".

Towards an imagery economy

The choice of the Living Silver team to share historical photographs for free through Creative Commons licences is part of a movement dating back to the early 2000s, when the first version of these licences was developed.

"On the one hand, there are the photos that cost €200 to be used once," says Kofler. "On the other, there is a different way of thinking, one example being the Europeana portal [which showcases digitised content relating to Europe's cultural heritage], where it is considered necessary to give people back the cultural treasure represented by historical photographs," he explains.

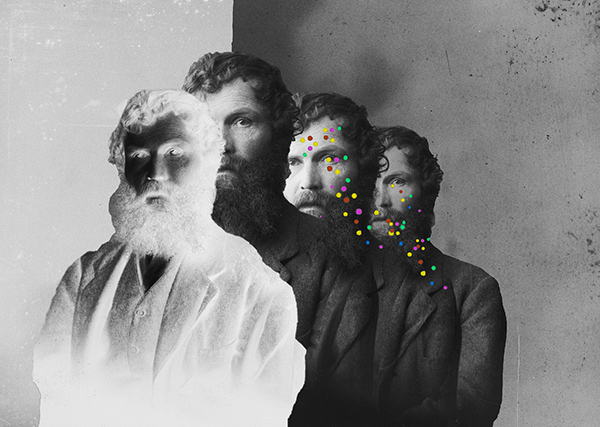

Historical photos come out of the archives and are put back into circulation for free, potentially giving rise to new creative processes. One example is the work of Claudia Corrent, a photographer working in the visual arts.

In recent years, she has focused on the creation of new photographs from the reprocessing of historical photos from the archives of private individuals or public institutions, including the Waldmüller trove of the Province of Bolzano.

Some of Waldmüller's images were the basis for Corrent's works created for the exhibition FLUX FRAGMENTS, Collection I. This opened at the end of May and was organised by the Bolzano-based cultural platform Lungomare.

The photos in question concerned rivers, the theme around which FLUX revolves. Its aim is to explore the river landscapes of the South Tyrolean capital and the public spaces around them.

"The discourse of reusing historical photos goes against the paradigm of photography as something definitive, demonstrating instead how photos can give us different meanings than those intended by the original author," says Corrent. "Moreover, since there is an enormous amount of visual stimuli in today's age, it is also a form of imagery economy: why not update old ones instead of producing new ones?"

In this way the photos of great-grandparents, or old Polaroids stored in shoeboxes in the attic, can be transformed into fresh works of art.

This article was produced as part of the Union Is Strength competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of the Union Is Strength competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.