No qualifications and no job: portrait of an invisible youth

In Toulouse and Rodez, in France’s Occitania region, “Second Chance Schools” are offering dropouts a place to rebuild their lives.

Toulouse and Rodez (France)

"I am proud of my career. To have got this far, and not to have ended up weeping under a bridge, or in prison, or in a psychiatric ward, or on the street, that's something." For years, Valentin had been doing one small job after another and going through a lot of hardship. Placed in care at the age of 6, dropping out of school and shuffled between a children's home and an unscrupulous foster family, Valentin entered adult life while still a teenager and by the back door - through choices that weren't really choices at all. "I was in the countryside, in the Gers, and there weren't many opportunities apart from construction or duck-farming, so I chose construction, but I didn't want to do that, I did it out of necessity."

One day, his counsellor at the employment office told him about the “Second Chance School” ("Ecole de la 2ème Chance", E2C), in Toulouse. This establishment, which opened its doors in 2004, supports young people who have dropped out of school and helps them reintegrate into society and the workplace. In a few months, Valentin completed a refresher course, obtained several internships, and found himself working at the Institute for Young Blind People in Toulouse. "For a long time, I had planned to become an educational counsellor, but I didn't know how to go about it. Later, I would like to work in a children’s home, but I think it's too early, I don't have the maturity for that yet", explains the 26-year-old, who seems to have finally found his place.

It was in the mid-1990s that a project emerged, in France and in Europe, to reintegrate young people who have left the school system without training. It was a European Commission white paper, "Teaching and Learning: Towards the Learning Society", presented by Edith Cresson in 1995, which laid the foundations for future action. "The idea was to create Second Chance Schools which would be grassroots schemes, based on local political will, bringing together local initiatives, stakeholders, partners and businesses. The aim was to offer differentiated support for young people for whom school was not a solution, so that they could be integrated into the knowledge society", explains Marc Martin, the director of the E2C Toulouse. There are now 135 such schools in France, supported by local authorities.

These schools help repair the damage caused by an imperfect school system which, under the guise of meritocracy and equal opportunity, has in reality led to the deferred exclusion of the most disadvantaged pupils. In Les Héritiers, Pierre Bourdieu already noted that schools reproduce social inequalities in their educational form. The Second Chance Schools are catching these excluded students: "We spend our time smashing the glass ceilings", says Marc Martin.

The problem of student precarity entered the public debate at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, as queues grew longer in front of emergency relief centres. But another group of young people remained under the radar. These are those known as NEETs, “Neither in Employment nor in Education or Training”, who are struggling to find their way through the administrative maze.

In 2019, they represented 12.9% of the population aged 15-29 in France excluding Mayotte, i.e. around 1.5 million young people, the majority of whom are women. This is slightly higher than the European average (12.5%), but far behind the Netherlands (5.7%).

"Our dads knew they could join a company and stay there all their lives. Now we live in a state of uncertainty: there's Covid, there's war... The whole world is under stress, says Valentin. For me, the children's home was a jungle. It makes you grow up fast, but it also messes you up. Fortunately, there were people who made us believe that it was possible to get out of that. It is these people who help you, by telling you that you are not so different from the others."

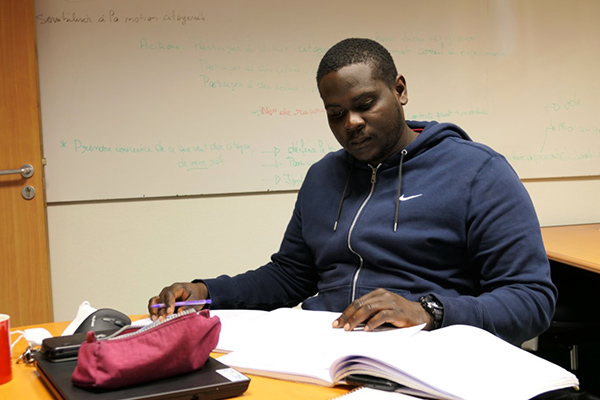

Finding stability

At the E2C, everything is done to allow young people to choose the path they want to take: guidance is no longer perceived as a punishment, which leads to better results. Occupations are discovered through a wide range of experiences, including workshops, meetings, internships, training courses and work placements. The aim is to break down the barriers of self-limitation, or just the lack of knowledge of what exists. In order to build a future, one needs to overcome the obstacles that may have arisen during one's life, which can be both material and psychological barriers.

Aged between 16 and 30, the students who arrive at the E2C are for the most part in a precarious situation and have gone through difficult experiences: early school drop-out, family breakdown, physical and sexual violence, isolation, disability, addiction, debts, exile, etc. "Nothing is stable in the lives of the young people we support. Here, they find a place, points of reference, and we listen to them, explains Béatrice Daunay, head of training and company relations at the E2C Toulouse. Our added value is to be able to keep track of them, by creating a close relationship based on trust. The pathway at the school is like a tailor-made programme. We are a kind of transitional space for adaptation and preparation for a stable professional life", she says.

The first few months spent at the school are used to assess the profile and difficulties of each young person, so as to lay the foundations for a new start. "We begin with a thorough examination of their personal situation: we have to make sure that all their rights are covered, carry out a health check, and identify the personal and social problems they may be facing. We also carry out an educational diagnosis, to see where they are in terms of basic skills in French, communication, mathematics and IT. Explaining to pupils that there are different types of intelligence makes them feel less guilty about their failure at school", says Béatrice Daunay. Marc Martin agrees: "I tend to say that they experienced failure at school, but it is not their fault: they were children, and the system did not know how to deal with them."

This failure of the system also represents a considerable cost for society, Marc Martin points out: "It is an economic cost, since it means a lot of unavailable skills and labour for companies; it is also a social cost, which has been put at €230,000 per young person, in terms of compensation, reparations, etc.; and above all, it is a human cost, for those who experience it."

Making a commitment over time

At the E2C Toulouse as in Rodez, where a second Occitan branch opened in 2017, the teaching teams take care never to devalue the students, and to work on rebuilding the self-esteem that they often lack. All of them have been trained in the ADVP method (Activation of Vocational and Personal Development), developed in Quebec in the 1970s. It is based on a process of educational choices that ultimately leads to a professional and personal career orientation. Although they play down some of the method's presuppositions, the trainers use it as a starting point to help their students emancipate themselves from the societal constraints that limit them.

Hired at the E2C Rodez in 2020 to act as a link between students and companies, Nicolas Guibal, a former sales rep, quickly noticed the gap between the idea he had of vocational integration and its practical implementation: "I didn't expect this at all. In my head, I imagined young people who were a bit lost, in trouble, and I said to myself, 'We're going to straighten all this out, it's going to be quick and tidy...'. With time, I realised that we all move at very different speeds in terms of understanding and accepting the situation, and our ability to move forward."

In practice, the question of pace is at the heart of the concerns of the Occitan E2Cs. The goal is sustainable integration. The programme lasts nine months in theory, and in practice as long as it takes for each person to see their project through. "We individualise each of the courses. The programme changes every week for a young person, we constantly adjust it to his or her situation. After nine months, if we leave them alone, all the work they have done may fall by the wayside, so we maintain a long-term follow-up", Daunay explains.

Ludovic can testify to this, having left the Toulouse school within three months to pursue training as an electrician at the company Enedis and the Toulouse apprentice training centre (CFA). He recently returned to the E2C after an incident that jeopardised his training. A few months before he was due to obtain his BTS, some of his classmates got him expelled following an altercation involving racism. His employer supports him, but it is not enough:

"I've been categorised as violent. I've been in this CFA for five years, I haven't even tried to defend myself. The last two years it was very complicated, I went there with a knot in my stomach, it was tiring, and psychologically exhausting. Some students complained that I created a bad atmosphere in the class because I didn't fit in, there was a form of harassment, I was called an animal... Someone weaker would have jumped off a bridge, I think", says this 30-year-old Guyanese, who remembers discovering racism when he arrived in mainland France. "I didn't know what it meant before. I quickly realised that I wasn't at home, even though I am at home. There are always little looks. When people first see me, I'm not French but 'African'. People look at me as an ogre. I know that I have the right to be here, I refuse to put up barriers, but if I had known what was waiting for me, I would have done everything I could not to come."

Despite his latest setbacks, Ludovic remains optimistic for the future: "I'm working independently to finish my BTS, and if I manage to do so, it will be by my own efforts. I'll have achieved something pretty big. Now when I wake up, I'm really happy to come to the school. In the end, this has given me even more strength. I tell myself that if so many people want to hurt me, and others are willing to support me, then I am worth something."

A European spirit

Many of the young people who go through the E2C have experienced uprooting, whether as children in care, or French citizens from overseas, or immigrants or exiles who have just arrived in France or have been struggling for several years to find a place there. Hamida arrived in France five years ago. After her marriage, she moved from Relizane, in Algeria, to the towers of Bagatelle, on the outskirts of Toulouse. "I don't speak French very well, she says apologetically from the outset. I'd like to discover places in Toulouse, learn the language... My husband is quite strict. Before, I didn't go out, I stayed at home, I was bored."

Since she joined the E2C on the advice of a friend, she has opened a bank account and convinced her husband to let her go out. But the former hairdresser and make-up artist from Algeria was turned down by all the beauty salons where she applied, and has had to turn to housework. Eventually, Hamida would like to work in a creche, with children. But for the time being, she is worried about whether she can ask at job interviews whether she can keep her veil, which she does not dare to name.

The Second Chance Schools also help to reduce the achievement gap between the children of parents born in France and the others, who do less well due to language-learning difficulties as well as their living conditions and the fact that their families do not master the arcana of the school system. The problem of NEETs cannot therefore be addressed solely at the level of France. However, France stands out in Europe because of its elitist school system, which increases inequalities between students, as the PISA programme reveals every three years.

In 1998, the first Second Chance School opened its doors in Marseille, and from the 2000s onwards, Europe began to finance schools throughout the EU. Each one operates according to its own system, but all of them try to set up common projects, sometimes with a focus on international mobility. In Occitania, the E2Cs of Toulouse and Rodez receive the majority of their subsidies from the region, the European Social Fund (ESF), and the French state.

Indeed, the ESF has invested massively in the vocational and social integration of NEETs, in particular through the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). Between 2014 and 2020, a total of €781 million was allocated to tackling unemployment among the under-30s. This is a substantial sum, but it still only covers around 20% of NEETs in France, with funds being distributed throughout the EU. Almost 40% of these young people, who are not followed by the state employment agency, are not even reached by these programmes.

Outside the walls

The strength of the E2C and its teams is also its integration into the local institutional and associative fabric, which includes local agencies, the family-planning service and NGOs providing assistance to migrants. Angélina Plassant, a trainer in charge of business relations in Rodez, is well aware of the commitments and limits of her role with the young people she supports:

"My objective is to work with people to teach them to develop their autonomy. It's a job of passion, which is obviously tiring, because you hear a lot of stories that you have to be able to convey, without judgement, and you have to find a balance. The idea is to say that we have enough partners around us to be able to guide the students on things that are not our responsibility. We are not doctors, psychologists or social workers, we are trainers and coaches. If we let ourselves be overwhelmed by things that are not our responsibility and we are not able to handle a situation, we can also put a young person in danger."

This does not prevent the teams from going outside the framework of the school when necessary and giving a hand after 5pm to those who need it. This was the case for Nafida, a 23-year-old Mahoran of Comorian origin, who arrived in metropolitan France in the summer of 2021. She ended up with her husband and two children in an unsanitary flat in Bellefontaine.

At the bottom of her block of flats, a few young people are hanging around waiting for the breeze to die down and the dealers to come. They can be found in the stairwell, casting a suspicious glance at Nafida, before she rushes into her flat and closes the door amid the strong smell of cannabis. "One day two people came to my door and asked me if I was a squatter or a tenant", she says. By the time she went to get a bill to prove her status, they had left with the keys lying on the chest of drawers in the hall. Months went by with strangers ringing her doorbell at all hours of the day and night, and breaking into her apartment in her absence, until a police raid on her flat revealed that the former tenant was a drug dealer.

"I filed a complaint twice, they did nothing. My husband is in the military, he's rarely here, and I was alone with my two children. I was scared all the time. Once they broke down the door with a hammer." After two weeks of demanding a change of lock from the agency, it wasn't until the E2C got involved that new locks were immediately fitted. "We're going through terrible things, we want to say it, but we're afraid, and they don't listen to us", says Nafida, who is now struggling with mould that has covered the damp walls of the flat. The agency is not doing anything about that either. "They must think: 'The lady is small, she's black, so we can do what we want. This is racist, because when white people have a problem, they don't stay in difficulty like this", she notes.

For Nafida, the E2C has become a kind of refuge, which allows her to escape for a few hours during the day from the ever-present wounds of a painful past and an overly anxious present: "We are all treated in the same way there, and we are accepted as we are, no one ever makes a joke about our origins. They tell us that it's possible to do different jobs, so you can fulfil your dream." In the future, she would like to work in early-childhood education, and has already secured two internships in the field.

For most of the students of the Second Chance Schools, their handicap was so great that the road to reintegration is long and tortuous. However, the school is proud of its 70% rate of positive outcomes. Most students leave with a vocational training course or a contract of more than six months in their pocket, as well as the promise of long-term support from their former trainers.

This article was produced as part of the Union Is Strength competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of the Union Is Strength competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.